BLACK LIVES IN ALASKA: JOURNEY, JUSTICE, JOY

On view April 30, 2021 - Feb. 13, 2022

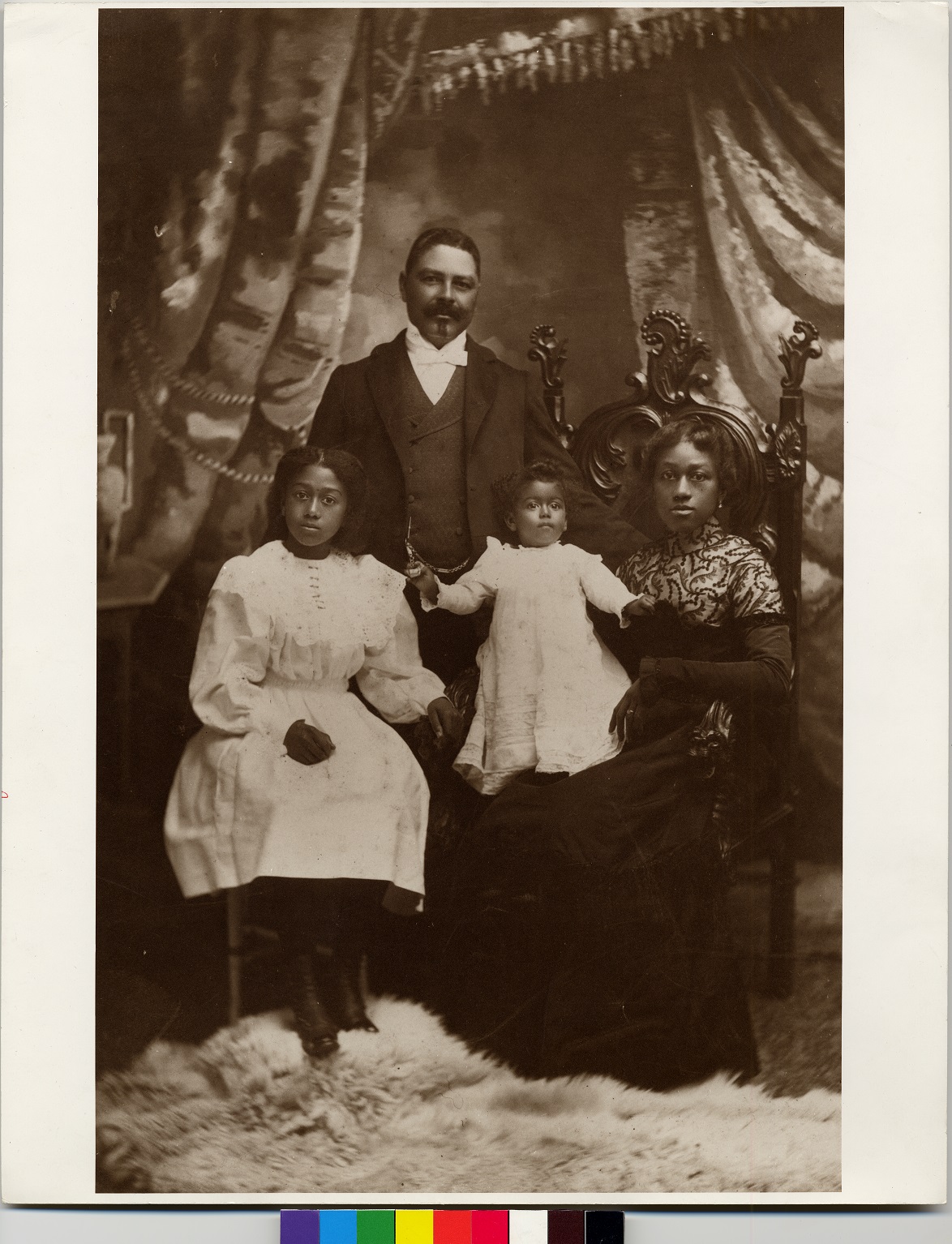

For over 150 years, Black individuals and families have settled or transited through Alaska. They patrolled the seas, built roads, served in the military, opened businesses, fought injustice, won political office, created artwork, and forged communities.

Historians have often emphasized the stories of Alaska’s settler population of mostly white, European-descended people who sought to claim and develop Indigenous lands. In this regard, Blacks in Alaska have occupied a different geopolitical station than they have in other parts of the country where they have constituted the largest and most visible minority population. Here, Alaskans of African descent have, at times, been targets of racial discrimination, but they have also found opportunities that eluded them elsewhere.

This online exhibition considers Black experiences in Alaska through the themes of journey, justice, and joy. Continuities with the larger, nationwide story of the Black freedom struggle are evident in these themes, even as they reveal the distinct and complex aspects of Black lives in Alaska. The images and stories gathered here enrich our understanding of Alaska communities, their diverse peoples, and our shared histories.

Black Lives in Alaska is comprised of photographs from archives across Alaska and across the US, as well as personal archives of several community partners. Also included are films from The HistoryMakers, the nation’s largest African American video oral history database. Spanning a period from the late 19th century to present day, images and ephemera communicate the rich histories and experiences of Black people in Alaska through views of everyday life.

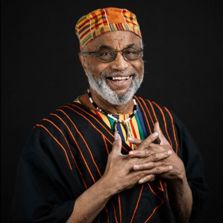

A panel of community leaders advised on the content, design, and development of this exhibition. We owe our gratitude for their invaluable insight, intelligence, and creativity, which gave shape to Black Lives in Alaska: Journey, Justice, Joy.

|

Cal Williams Photograph courtesy of Jovell Rennie, 2021 |

Celeste Hodge Growden Photograph courtesy of Jovell Rennie, 2021 |

Jovell Rennie Photograph courtesy of Kerry Tasker, 2021 |

Natasha Webster Photograph courtesy of Natasha Webster, 2021 |

Ian Hartman, PhD, advised on content and historical scope of the exhibition. We thank Natasha Webster for her contributions to the design of this exhibition.

We would also like to thank Eleanor Andrews for her generous support, as well as Ed Wesley and Samuel Fleming for the contribution of personal archives.

Journey

Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Oakland—these are just a few cities associated with the Great Migration, the movement of millions of Blacks from the South to urban centers of the Northeast, Midwest, and Pacific Coast. Anchorage, and Alaska more generally, is seldom included on that list. Yet, for the thousands of Black individuals who have called this state home, their Great Migration story has led them to Alaska.

Image: Neighbors, Anchorage, ca. 1960. Anchorage Museum, Samuel Fleming Collection, B2021.002.8.

Great Migration

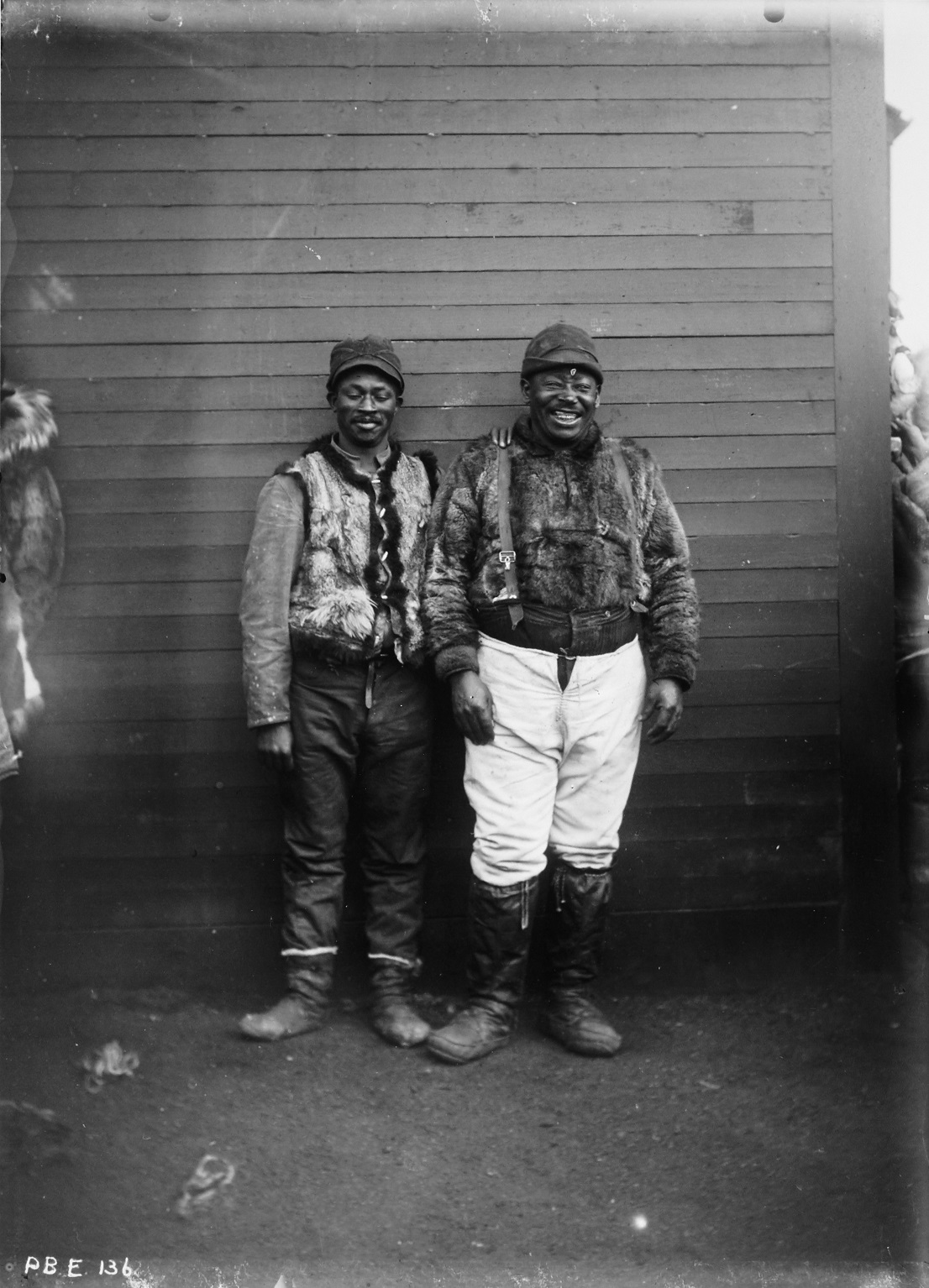

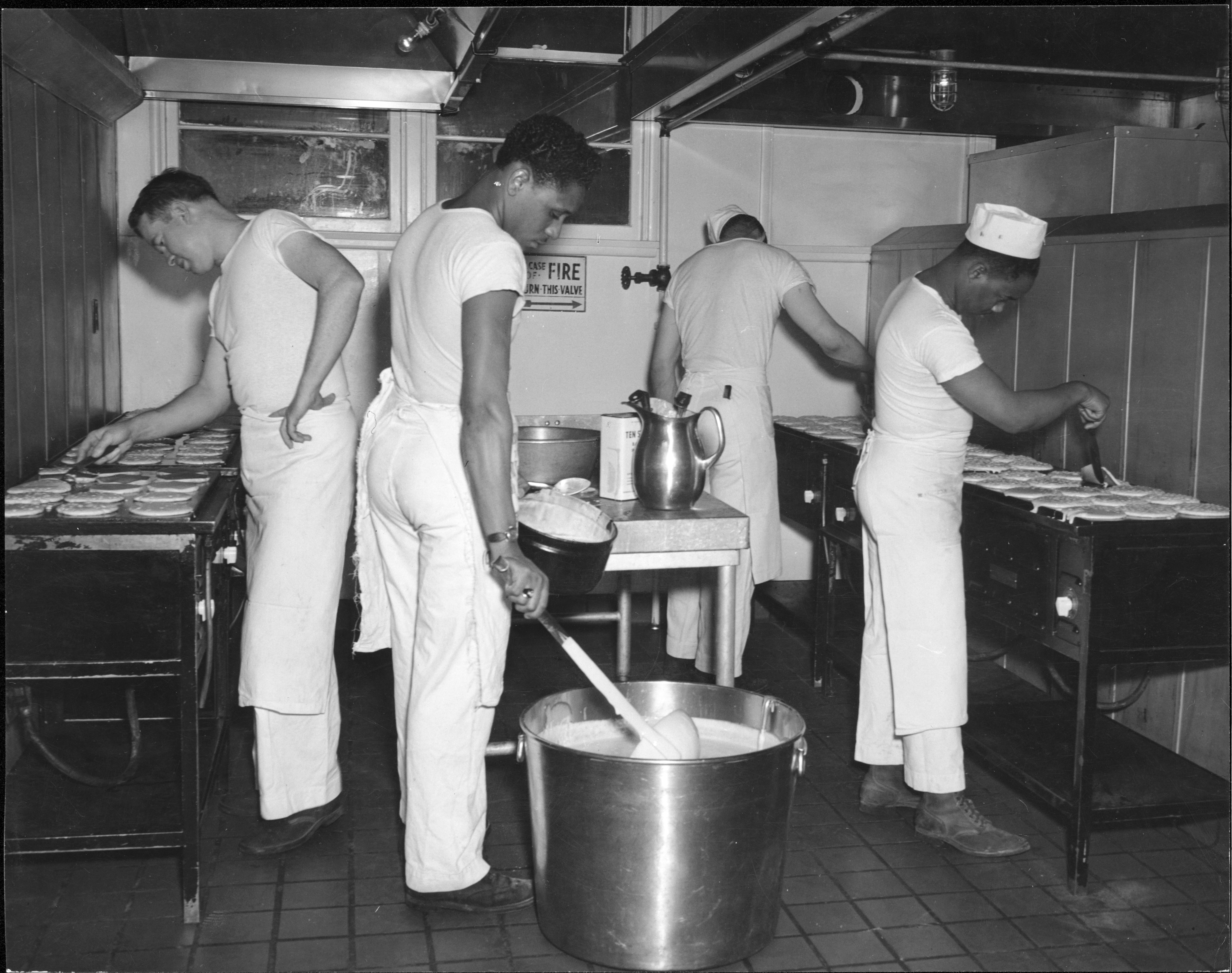

Black whalers were among the first non-Indigenous North Americans to view Alaska’s shores and ply its waters in the mid-to-late 19th century. Buffalo soldiers, Black soldiers who supported post-Civil War Westward expansion by the US government, arrived in Alaska at the turn of the 20th century along with throngs of prospectors who headed into the Interior and Canada in search of gold and fortune. Still others “mined the miners”—establishing inns, restaurants, brothels, and other businesses to seize on the influx of potential customers. Soldiers, sailors, and airmen arrived in Alaska throughout the 20th century, most notably during the Second World War. They were instrumental to the construction of the Alaska Highway, served in the Aleutians, and assumed positions throughout the territory to defend the nation’s most remote outposts.

Black in the Business World

While military service has brought many Black families to Alaska, the Alaska Railroad, the construction of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, commercial fishing, and the oil and gas industries have all drawn people North. Beyond these typically male-dominated professions, Black women have made their mark in law, medicine, government, business, and education—many of them leading the way in their fields. The journey that brought thousands of Blacks to Alaska echoes a broader story of the Great Migration; it is one of opportunity, perseverance, trial, and success.

Click to Enlarge

Justice

Activism driven by resistance to colonial and racial oppression has helped to shape Alaska. Black Alaskans have taken to the streets, but also to city and town halls, the State Capitol, corporate boardrooms, and courtrooms to assert their rights and call out injustice, similar to efforts elsewhere in the US. Alaska’s Black activists protested housing and employment discrimination and advocated for greater accountability in law enforcement, at times forging alliances with Indigenous, Asian, Pacific Islander, and white allies.

Black Civil Rights in Alaska built on the momentum of ongoing Alaska Native activism and advocacy. In 1945, Alaska Native peoples successfully promoted the passage of the Equal Rights Act, an early measure by the territory to limit race-based discrimination in public places. In the 1960s, as the Civil Rights movement was gaining steam throughout the US, Alaska’s communities of color fought and won significant victories.

Image: Young organizer at the Black Lives Matter rally in Anchorage, 2020. Anchorage Museum, Branstetter Collection, B2021.1.

Civil Rights Movement

Black activists along Alaska’s railbelt, the urbanized stretch of the state extending from Seward to Fairbanks, took up causes associated with the civil rights movement. Job security and employment discrimination, access to housing, and inclusion in politics and business represented some of the prevailing concerns.

Quest for Equality

Racism in the U.S. is structural, which means that patterns of discrimination are persistent and embedded in our legal, educational, health care, and economic institutions. Many Black Alaskans remain engaged in the quest for equality and have joined a diverse coalition to build a more inclusive Alaska in the 21st century, one with equity and justice at its center.

Click to Enlarge

Joy

Black individuals who settled in Alaska built durable cultural institutions, churches, and businesses. Beyond recognizable modes of activism and resistance to discrimination, the presence of joy shared among friends, colleagues, and families is a testament to the love within Alaska’s Black communities.

These images capture subtle and routine moments of joy, from an evening date night to purchasing a new car or a first home. They showcase outdoor recreation and organized sports, weekends at the Alaska State Fair and Sunday morning worship. In sum, they present a history defined as much by intimate connections, familial bonds, and celebratory gatherings as struggles for justice.

Image: The Alaska Black Caucus’ Fourth Annual Awards Banquet, 1980. University of Alaska Anchorage Collection, Alaska Black Caucus, Inc. records, 1975-1993, UAA-HMC-0003-b7-s5-p13-2.

Creative Expression

These images convey the subtly defiant and creative ways in which Black individuals respond to continued discrimination. Representations of Black joy, pleasure, and leisure are an embodiment of resistance and a way to hold space for a politics of liberation.

Click to Enlarge

Activate: Digital Interactive Cards from the Exhibition

The HistoryMakers

The HistoryMakers is a national 501(c)(3) non-profit research and educational institution committed to preserving and making widely accessible the untold personal stories of both well-known and unsung African Americans. Through the media and a series of user-friendly products, services, and events, The HistoryMakers enlightens, entertains, and educates the public, helping to refashion a more inclusive record of American history.

See what some of our Alaskan HistoryMakers have shared: