Her husband was dying of COVID

By Julia O'Malley

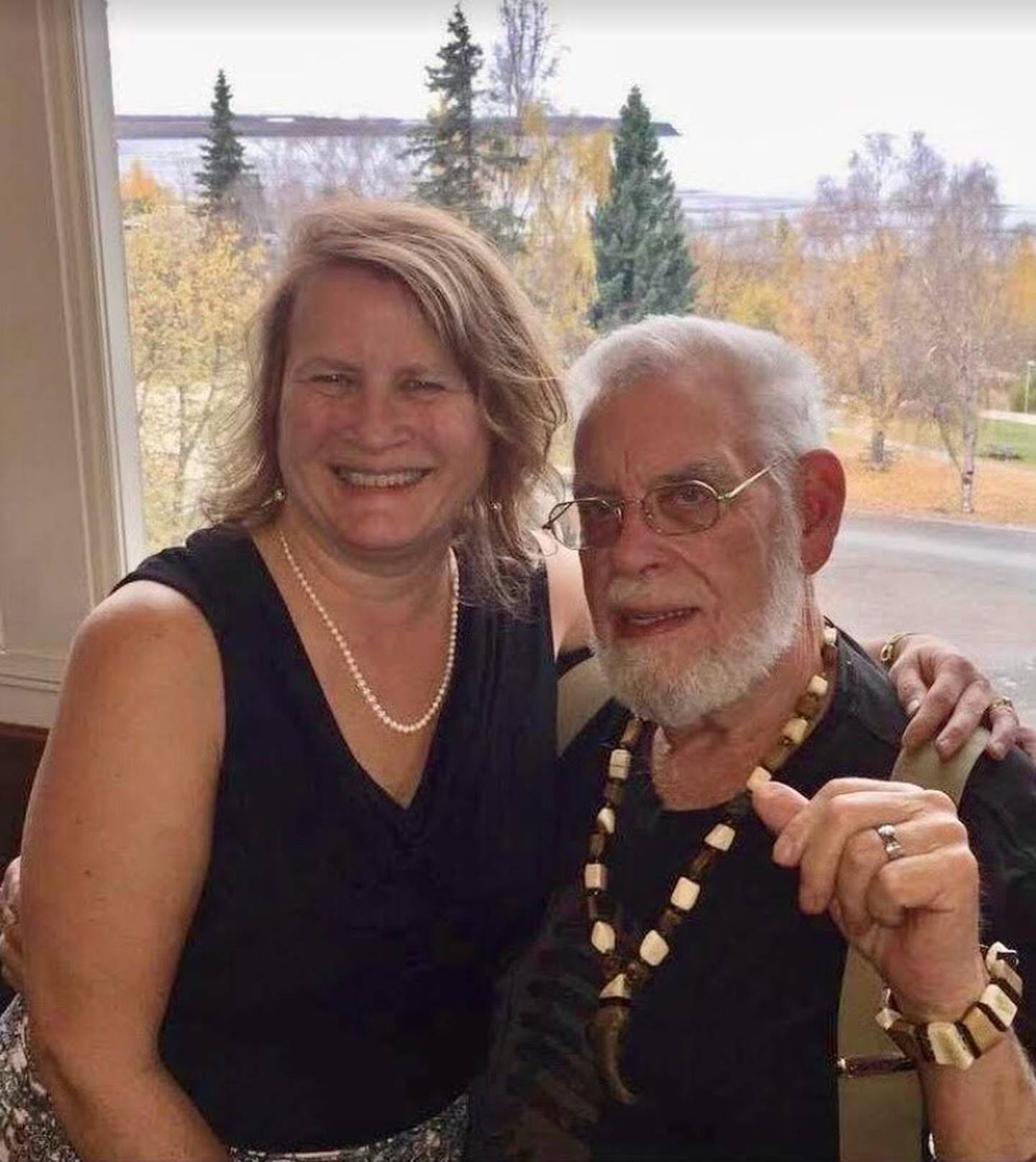

Wendi Gratrix lost her husband of 36 years, Speed, to coronavirus in September. The story is nightmarish, but she always tells it as a series of small mercies.

A few hundred people in Anchorage know Wendi, a 64-year-old office administrator, as “Lady Wendi” on Twitter. She joined the platform in 2008 to keep track of Sarah Palin, and many of her Twitter friends have known her since. For all the bad vibes on the internet, Wendi makes a habit of sending good ones. She’s the first person to like every kid’s first-day-of-school picture. Post a gorgeous latte or a perfect avocado, she’ll answer with a fire emoji. If you write about a rough day, she’ll check on you later.

“Wendi is sort of like the queen of Anchorage Twitter,” said Emily Purrenhage, a pharmacist and roller girl who befriended Wendi on the platform years ago when she moved to Anchorage. “She takes us little transplants under her wing. She’s kind of like an auntie.”

Speed had a Twitter account too. His given name was Erldon but he’d been known as Speed since he was born two weeks earlier than expected in 1942. He was the sort of fellow you’d recognize as from here – tall, bearded, with a preference for flannel shirts, suspenders and a pistol within reach. All his working life, he’d been an electrician. As a hobby, he carved ivory, which is why he always wore a beaded necklace strung with a single bear claw.

Wendi and Speed made their home in Spenard, where Speed lived since childhood. Wendi’s Twitter followers knew their comings and goings. In the summertime, she convened small cocktail parties on her deck while wearing a tiara and a little sequins. She had a fluffy cat named Ping Pong. She cared for her elderly mother, called “Queen Mum.”

On the other side of the isolation of the last two years are the people we hung on to. Wendi hung on to her Twitter friends, when her real life friends couldn’t visit anymore. And, when she needed them, they hung on to her too.

The Twitter friends were among the first to hear when Speed started to feel ill in late August. He had heart trouble and lung trouble and laboring all those years hurt his back. He hadn’t been in favor of getting vaccinated but eventually gave in, she said, because he knew he was vulnerable. He tested positive first. Then she did.

Not long after she tweeted about it, flowers arrived from a Twitter friend up in Fairbanks, wishing her a fast recovery. A professional arrangement! Wendi was blown away.

Her condition improved. But Speed couldn’t catch his breath. His doctor called and told them to go to the ER. But, by then, Wendi couldn’t get him to the car.

“I called 911,” she said. “And Station 5 came over with their heroes.”

Paramedics arrived in minutes, decked out in hazmat gear, and coaxed Speed on a gurney.

“And while I was dealing with the intake fireman, I could hear the paramedics start to holler, ‘Speed come back, hey buddy, hey buddy, come back.’ ... I could tell that it sounded like he’d passed out,” Wendi said. “So I went down there and I was rustling him and talking to him and calling his name and his eyes flickered back. … That was the last time I was able to touch him, or, you know, talk to him personally.”

A little over a week passed with Speed at Alaska Native Medical Center. There were no visitors. Wendi waited each day for a nurse to call. Meanwhile, the Twitter friends began a quiet campaign. She’d hear footsteps on her deck. A knock. There’d be a dozen fresh eggs. A gift card for dinner. A bottle of gin.

“People I’d never met!” she said. “Showing up and bringing me things.”

The doctors put Speed in a prone position, switching him from his stomach to his back to help his breathing. Toward the end of the week, the nurse who had called her every day told her, gently, his numbers didn’t look good.

“He says, ’I’m not giving you hope,’” she said. “Speed was really, really bad.”

It broke her heart. But, looking back, honesty was an act of kindness. It helped prepare her for what would come next.

She tweeted the news. Purrenhage brought her soup and biscuits. Liz and David Nicolai, a librarian and a mechanical engineer, brought her nacho fixings and queso straight off the stove. Natalie Stefano, a data manager, brought her a bag of easy-to-eat snacks.

“Anything my heart desired, they showed up with,” Wendi said. “They just seem to know.”

Speed’s daughters came. They said goodbye in the grim manner of so many families during the pandemic: via video on a tablet held by a nurse.

“We were just robbed of all that end-of-life intimacy, you know?” Wendi said. " I wasn’t able to hold his hand or feel his warmth or whisper in his ear.”

She gets teary talking about the doctors and nurses who walked with her through it.

“One nurse said that, you know, she talked to him all the time, just spoke out loud to him, just let him know he was doing good and he wasn’t alone,” she said.

Wendi estimates 50 people she knew from Twitter sent or delivered gifts since she and Speed got sick. Dozens more of her real life friends reached out too.

“My feelings?” she wrote in a Twitter message. “Each loving kindness helped to push my grief and shock to a different place so my heart could process. … Was like a big virtual hug never breaking off.”

A few days after Speed died, Wendi went to Jackie’s Place, where they had been regulars. She ordered some breakfasts to send to ANMC’s COVID ward.

“And I reached for my card, Janice wouldn’t take my money,” Wendi said. “And she sent out at least 25 of those breakfast orders to the crowd (at ANMC) and delivered them.”

Restaurant owner Janice Johnson delivered the meals herself.

“(If) the tables turned she would absolutely have done the same,” Johnson wrote in an email.

Speed will be buried this summer at Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson. Wendi still wakes up sometimes and forgets he’s gone. This is the loneliest time, six months out, when you still have to sort through clothes and get used to making dinner for just yourself. But just when she needs to be reminded she’s not alone, Wendi still finds gifts on her doorstep.