Sound and Story: Alexis Anoruk Sallee

March 04, 2022

By Francesca Du Brock, Chief Curator

Filmmaker Alexis Anoruk Sallee was born and raised between Anchorage and Eagle River. On her father’s side, she has roots in Sitnasuak (Nome) and Kigiktaq (Shishmaref). On her mother’s side, she is Mexican from Tepic, Nayarit. Growing up in urban Alaska at a distance from many of her Inupiaq traditions, Sallee uses her creative practice as a way of learning about and connecting with her cultural heritage, as well as a means of platforming stories centering Indigeneity, queerness, and female strength.

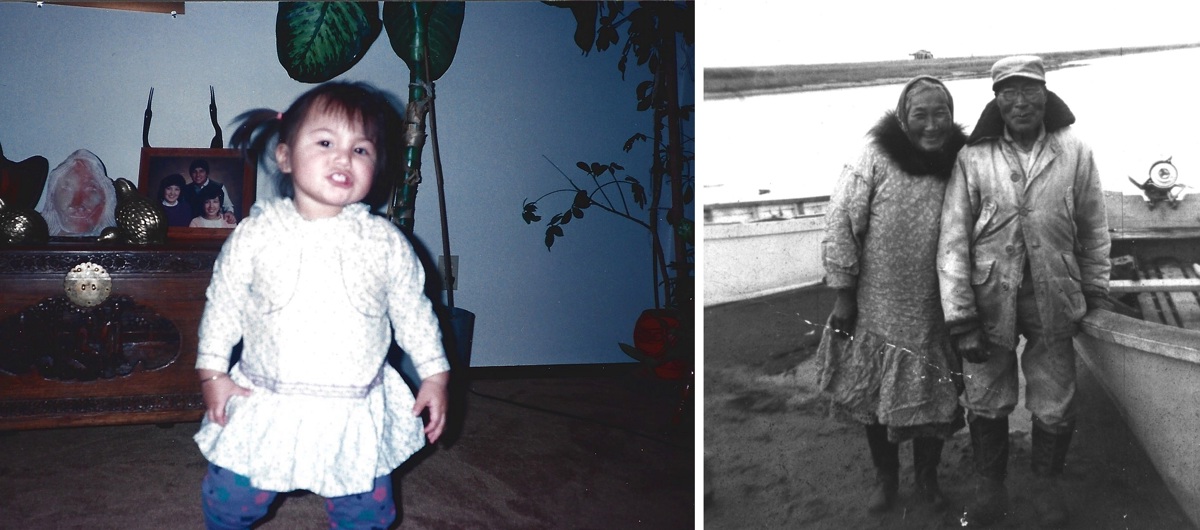

Left: Sallee as a child in her grandparent’s home in Anchorage. Right: Sallee’s great grandparents, Lena and John Ahnangnatoguk, September 1956.

Sallee found her way to filmmaking through an early interest in audio engineering honed as a teenage volunteer at her local public radio station. “I wasn’t really a good student, so I gravitated towards being creative,” Sallee says. She was a shy kid and enjoyed long hours spent in a room alone as she edited interviews. This early passion led her to study recording arts, and eventually pursue a career in Los Angeles working on sound design and mixing for Hollywood films.

Working within the film industry on major productions with many other creatives, Sallee began to question the homogeneity of stories being represented. She realized that if she ever wanted to see stories about people she knew, other Indigenous people, or queer Indigenous people, she was going to need to “step up and create opportunities myself.” Sallee transitioned to producing, directing, and shooting her own films. Her first big project, The Definition of Resilience, documents the cultural teachings of Indigenous hip-hop artists in Alaska and the Lower 48.

Sallee in the field filming the “Alaska” episode of Definition of Resilience with Samuel Johns in Kluti-Kaah

Follow along with Alexis Sallee’s residency for the month of March via the Anchorage Museum’s social media channels and stay tuned for her livestream studio demo at noon on March 30, 2022, on Facebook Live

For Sallee, there is a clear linkage between her work in sound design and her identity as an Inupiaq woman. Inupiat culture, she says, was preserved through story and song. “When a group performs a traditional song, they might imitate the sound of seals or birds in our homelands…these are the first examples of sound design, passed down through the generations. It’s always been a part of my background and I’m just starting to realize that now.”

When conceptualizing a new project, Sallee often starts with audio: a song, or a natural sound from the environment. For her, sound is the emotional way into a subject, and the primary way she likes to connect with her audiences. For her short film about Inupiat culture and womanhood, Who We Are, she started by thinking about the sounds of the land at her aunt’s fish camp. “I’m standing there and I am hearing the waves hit the beach and the wind. I picture what it’s like to be inside the fish camp, where you hear the wind blowing outside, and the birds.” This immediacy of these physical sensations communicates an intimacy with land that is the crux of Sallee’s story.

Left: Sallee and collaborators filming Who We Are at her Auntie Donna and Uncle Brian James’ fish camp in camp in Nome. Right: Mentoring youth at Media Makers session during the 2019 Alaska Federation of Natives Elders and Youth conference.

Sallee sees her work as an opportunity to educate and inform publics that have been misled about Indigenous cultures and histories. While some people might use facts and reportage to correct harmful legacies, Sallee says she prefers to do it by reaching people on an emotional level: “I think that people’s perspectives can change when they start to see and feel what that person on screen is feeling also.”

Sallee also hopes to use her projects to create opportunities for Native people to learn different aspects of film production. In 2021 she worked with Native Movement to facilitate their first-ever Alaska Native Filmmakers Intensive, which included Indigenous storytellers from all over the state. “I think it’s a very exciting time to be a person of color making original stories,” she says. For herself, this has been a healing journey of connecting with her own culture and learning the stories of her family: “I recognize who I am, where I come from, and what kinds of stories I want to tell.”

Support for this Virtual Artist Residency has been provided, in part, by the Art Bridges Foundation.

Header image: Alexis Sallee. Image by Tomás Karmelo Amaya.