Family History and Material Process: The Art of Theresa Woldstad

January 26, 2022

By Francesca Du Brock, Chief Curator

Artist Theresa Woldstad grew up traveling all over Alaska with her mother and father, a second-generation fish and wildlife enforcement officer with the State of Alaska. Woldstad describes herself as “a modern Native,” meaning that her family history is complected by colonial forces of displacement, resettlement, and capitalism. Her maternal grandfather, an American Indian entrepreneur and early settler in Alaska, helped found the town of North Pole. Mining themes of contradiction and cultural blending in her work, Woldstad delights in these strange twists within her own family tree: “it’s a bit of a joke in our family that you have this Indigenous guy, and industrial welder, who came North to an area where he essentially became a pioneer/colonizer.”

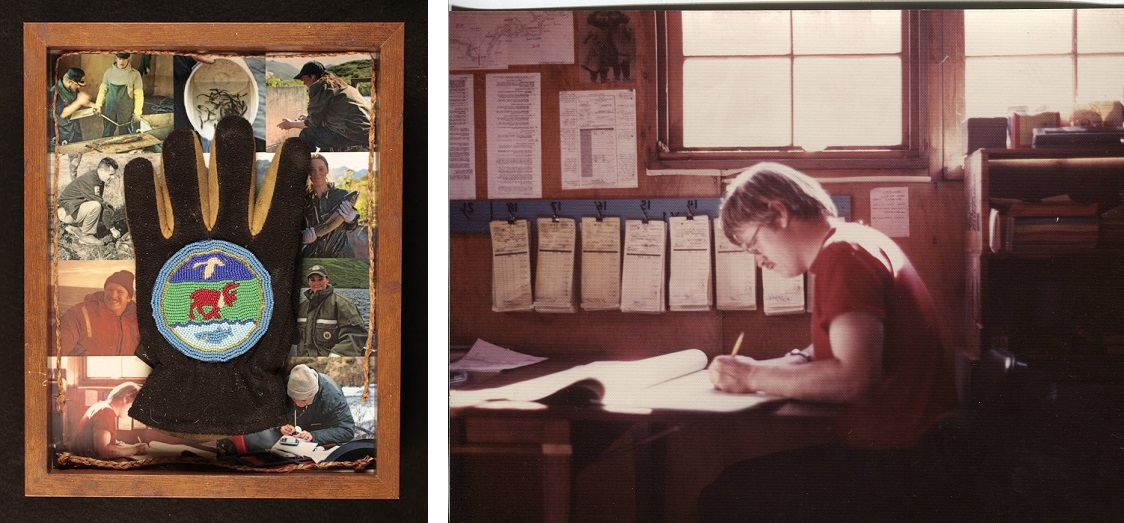

Left: Woldstad recording field notes regarding aquatic insects at Aleknagik lake, 2004. Right: Woldstad weaving a cedar bark basket at Frazer Lake on Kodiak Island during her downtime in the field, 2011.

Having lived for periods of time all over the state, Woldstad is well-versed in the geographical and cultural diversity of Alaska and has studied under renowned elders and artists from nearly every tribal region. Working with natural materials and often employing customary techniques, it’s at times difficult to articulate her positionality towards the art that she makes. She is careful to clarify “I am a Native artist in Alaska and a registered member of a Native American tribe in Alaska, but I am not an Alaska Native artist. The story I’m telling is very uniquely my own. I’m telling the story of my life, my father’s life, and my mother’s life, while honoring the people who took the time to teach me.”

Left: Government Hands, 2018. Materials include a wood frame, old winter work gloves, glass and plastic beads, yellow cedar bark, and photos of the artist, the artist’s father, and family friends working as ADF&G fisheries technicians and game officers. The photo on the right is of the artist’s father, Ken Woldstad, working as an ADF&G fisheries technician, entering commercial fish tickets at Emmonak on the Yukon River in 1977.

Studying art as well as biology and fisheries management, Woldstad followed in her father’s and grandfather’s footsteps, becoming the third generation in her family to work with the Alaska Department of Fish & Game. Evolving as both a scientist and artist simultaneously, she reflects that “there is an art to science and there is a science to making art.” Her parents never made a distinction between creative thinking and analytical thinking, and she enjoys blending the two realms of her life in her practice. In her work Government Hands, she juxtaposes one of her father’s beaded work gloves against photographs of her father, grandfather, and herself conducting wildlife studies. “People often say that the government ‘has its hands on everything,’ and think of it as this unknowable, impersonal force…But I knew all the wildlife officers and grew up around them.”

Many of Wolstad’s works draw upon her experiences as an Indigenous person and a wildlife researcher, interrogating areas rich in contradiction where the logic of the natural world collides with state-mandated regulation and Indigenous custom. Federal Caribou and State Caribou (header image) depicts animals migrating freely across human-imposed borders, pointing out the flaws of some regulations when they fail to account for the interconnectedness of ecosystems or to respect longstanding Indigenous harvest practices.

Other works, such as Non-timber Forest Products and Study of Ptarmigan, delight in the aesthetic value of raw materials while also slyly poking fun at regulatory language designating what qualifies as Alaska Native art. Legally, Alaska Native art is defined as “a finished product that has been substantially altered to increase its monetary and aesthetic value from an unaltered natural material by skillful hands.” In these works, Woldstad creates from materials that have expressly not been significantly altered, drawing attention to the ambiguity of such language and the challenges many Native artists face in navigating regulations governing their art production.

Left: Non-timber Forest Products, 2019. Materials include rye grass, cedar bark, spruce roots, birch bark, diamond willow, and spruce wood. Right: Study of Ptarmigan, 2017. Materials include ptarmigan wings, tails, and feet, dyed red cedar bark, glass beads, and birch bark.

In another piece, Black Bear Square, Woldstad employs the same logic to make a tongue-in-cheek comment on materiality and artistic intent. Referencing Kazimir Malevich’s 1915 painting Black Square, an icon of early Modernism, Woldstad created her version by cutting a perfect square from the hide of a black bear. The fur naturally spills over the borders of the precise edge, highlighting the physical presence of the material and questioning why we might read a painted black square as a work with inherent conceptual value while Indigenous artworks created from natural materials are subjected to complicated hierarchies of categorization.

Ultimately, Woldstad’s work teases out such contradictions as a means of drawing attention to the complex realities of making art as an Indigenous person in Alaska today. She also draws on her experience working with ADF&G and the State of Alaska to help provide access to information so that Native artists can be informed and empowered to make art on their own terms.

Black Bear Square, 2020.

Support for this Virtual Artist Residency has been generously provided by Art Bridges. Follow along with Theresa Woldstad’s residency for the month of February via the Anchorage Museum’s social media channels and stay tuned for her livestream studio demo in late February.

Header image: Federal Caribou and State Caribou, 2020. Materials: basswood, velvet caribou antlers, wood drum frames, acrylic paint, caribou and muskox hair, caribou hide and sinew.