WE CAN ASPIRE TO CREATE A FUTURE WE DESPERATELY WANT TO FEEL AND FIND

By Julie Decker, Director/CEO, Anchorage Museum

"The work of art is a scream of freedom." - Christo Javacheff

In 2001, I watched a documentary film about artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude and their monumental, environmental artwork. The day after watching the film, I called NYC information and asked for the phone number of Christo Javacheff. He was listed. I invited Christo and Jeanne-Claude to Alaska.

I remember so much about their visit, now almost 20 years ago. They sent instructions ahead of time: they needed to fly in separate planes, sit in the back seat of a car, avoid greasy foods. But those rules were discarded on the ground. They sat in the front and ate a lot of greasy food here, with great spirit and generosity. We spent a lot of time together traveling the state. Christo was quiet, kind, warm and brilliant. He asked questions about everything—the contagious curiosity of an artist. He wore his signature “safari” jacket everywhere.

Later, in 2005, I worked on The Gates project in NYC. For two weeks, I helped erect gates in the northern part of Central Park with a small team. We were trained at a warehouse in Queens, then set out on buses each morning to our designated part of the park. It was cold most days, with the dark brown of February (the artists liked the contrast between the leafless trees and the orange fabric of the gates). The park was quiet and mostly empty as we constructed. When Christo and Jeanne-Claude walked by, they were treated like rock stars. The day The Gates opened to the public (23 miles and 7,503 gates), millions of people came out to see it—on foot, on bicycles, in horse-drawn carriages, with hands held and baby carriages. It went from being an artist project, constructed in quiet isolation, to being owned and embraced by the public. I remember clearly the joy of the people experiencing it. The Gates were in place for 16 days and then removed—part of Christo and Jeanne Claude’s belief that the ephemeral made things more treasured in memory.

In 2016, I saw my last Christo installation, The Floating Piers, in Italy on Lake Iseo. Jeanne-Claude had died in 2009. This was Christo’s last major project and one of few without her. There were concerns about too many tourists in the small town, but walking those piers, present again was joy. It was, simply, an experience--and a shared one. People, walked, sat, lunched, sang on the orange walkways, rejoicing in walking on water. It was transformative not of a landscape, but transformative in how it made us experience that landscape and each other within it. The power of art to bring people together for a fleeting experience was a testament to humanity. We seek those moments today.

Some people saw Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s ambitious proposals as unnecessary, excessive, extravagant, arrogant, invasive. Christo said it only appeared as monumental because it was art. Christo Javacheff died May 31. He was 84.

This death, too, marks 2020. It comes during a weekend of protests and riots, in the week of the death of George Floyd in the Powderhorn neighborhood of Minneapolis, in the week when the US topped 100,000 deaths due to COVID-19. And in the week of the latest “moonshot”—two NASA astronauts shot into space by SpaceX and now docked at the International Space Station.

It is in this time that we look for things that can have reach and resonance, we look for purpose and responsibility. We look for catalysts for regeneration, for places where all sections of the community can have a voice. We live with conflict, craving the recognition of what it is to be human.

It is in this time that we crave aspirations, a new view that we can embrace, surround. In an interview before the SpaceX launch, scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson encouraged a cosmic perspective—the advantage of seeing Earth as one, from far away, from outer space. He encouraged us to think about what drives civilization and to find the hope for ourselves and each other.

Buckminster Fuller called it Spaceship Earth in the 1960s—new strategies intended to enable all of humanity to live with freedom, comfort and dignity, without negatively impacting the earth’s ecosystems and emphasizing the common plight of humankind and life. "I’ve often heard people say: ‘I wonder what it would feel like to be on board a spaceship,’ and the answer is very simple. What does it feel like? That’s all we have ever experienced. We are all astronauts on a little spaceship called Earth,” said Fuller.

The pandemic, the protests and the riots, the rhetoric, the Twitter wars, the election, the astronaut launch, the zombie fires of the climate crisis—these things will change us and our world. The novel virus will prompt us to find novel ways of coping. We seek new ways of problem solving for all of Spaceship Earth.

In times of pain and trauma, we know that art and creativity are a form of healing and hearing, resilience and resistance, and that creativity and invention help lead us forward. But people can’t heal without first a recognition of the pain. This moment is profound. 2020 is on the record books and we are yet halfway through it. We lost people to the virus, to strife, to injustice. We have lost mothers, fathers, daughters, sons, sisters, brothers, friends, doctors, nurses, athletes, astrologists, journalists, novelists, musicians, artists and many others. Author David Levithan said, “What separates us from the animals, what separates us from the chaos, is our ability to mourn people we’ve never met.”

The stories we love, the videos that go viral in the joyous ways, have been the ones of humanity—of song, of dance, of creatures and comfort, of food and family, of nature and newborns. Art and creativity have healing powers—something we are reminded of over centuries. Throughout the pandemic, people have made, grown, sewn. Art is a symbol of our humanity. Christo once said, “The work of art is a scream of freedom.”

The progress of human civilization has long been about aspiration rather than contentment and passivity. We are living in a time when lives are being cut short from a virus and from violence, when the aspirations of others have been lost. We can play a role in aspiration—aspiring for a future we desperately want to feel and find—as this weekend we looked for it, whether in the form of a Dragon spacecraft or in a wish for the return of dreams and laughter—of shared joy. Crises generate innovation and creativity. Finding the sustainable future will be difficult. We will need to be more creative. We will need to reach beyond our corners and our comfort.

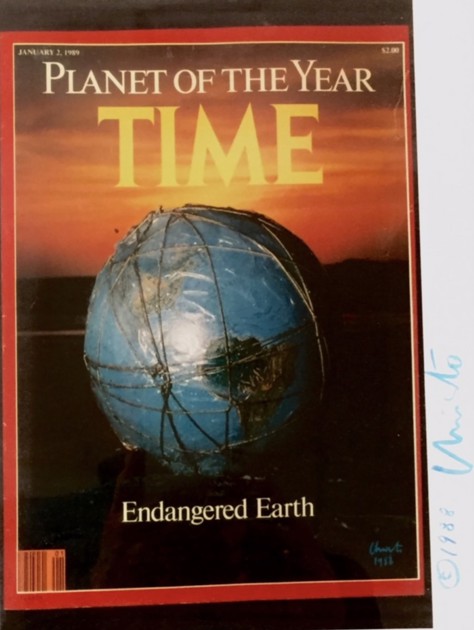

For years, I sent Christo and Jeanne-Claude Alaska king crab legs in December. Despite the rule of no greasy foods, one night we spent time at a Juneau restaurant with a group of Alaska artists, after visiting eagles and a glacier, and Christo and Jeanne-Claude talked about our landscapes as they dipped crab legs into melted butter Christo would, throughout the years, send me and my dad small gifts. He sent a cover of Time Magazine to my father. The image, from 1988, is a wrapped Earth. The headline is: Planet of the Year: Endangered Earth.

We need to ask big questions: What is our new giant step for (hu)mankind? We just sent astronauts into space on an Elon Musk dream. Christo, Musk and Fuller all made the cover of Time Magazine—creators of our times, however flawed, fallible and futuristic. Buckminster Fuller said, “If humanity does not apt for integrity, we are through completely. It is absolutely touch and go. Each one of us could make the difference.”

What’s left is to try. To work to understand, to celebrate lives and ideas and imaginations as we regret and remember. We recognize—the land, the people, the past and the future. We listen, mend, learn, do better.

Christo’s artwork had no precedent. We speak to the moment we are living in today as unprecedented, so today we look for the visionaries, the leaders, the creative minds who can lead us to a better tomorrow, however monumental.

As a museum, we are a place that celebrates ideas and imaginations, that preserves creativity and highlights risks and inventions. A museum is a place that celebrates the advancements of civilizations and that has an obligation to remind us of the moments to regret and remember.

We are a place with reach and resonance, so we must consider our purpose and our responsibility. Museums today have a role in supporting the development of communities. Museums can be a place to help shape community identity and bring different community groups together. They can be a catalyst for regeneration. Museums are striving to be places where all sections of the community can have a voice.

Today, we are a museum in a pandemic—a time of uncertainty and anxiety. As we focus on gently reopening, we consider logistics and mediate anxieties, but concurrently, we are called to consider this broader moment, to consider our community, our country and our world. We have worked to be an institution that thinks beyond the doors of the museum, but we always have more work to do. We have prompts and questions we can ask:

How do we help people feel, respond, see, listen, hope, recognize?

What are we investing in? With whom?

What stories are we telling? Are they the right stories for our time? Do we tell them in our traditional ways, the ways to which we are accustomed, or do we invent and employ new methods and platforms?

How do we think differently about our spaces in order to best serve our community in this time, in this place?

In what ways should we as an organization, as an institution dedicated to culture, be visible? How do we help others be visible?

How can we be of service to unity, camaraderie, cohesiveness, hope and direction?

How do we best contribute to wellness for ourselves, each other, and our community?

How do we best reflect our society’s pluralism and provide for a multitude of human experiences in every aspect of our operations and programs?

What values will we uphold for the community and for ourselves?

How can we help people feel the human at a time when so much feels inhumane?

How can we make a difference? How can we be useful?

How do we help fulfill and encourage aspirations?

What are we inventing?

What is our moon shot?

We live with conflict—ideas of advancement and regression, unrest and vision. We live without a shared vision for the future. Perhaps we can help people find aspiration—including aspirations for and recognition of what it is to be human.

It is a transformative time, but for transformation to be positive, we need positive leadership—in communities, in institutions, in all of us. Change is needed, so what is our best vision for Earth?

We commit to relationships that are based in honesty and trust (which takes time). We commit to authentic, reciprocal community engagement as the basis of a healthy and sustainable ecology of participation. We recognize our dependence upon the participation of community members as leaders, staff, program participants, volunteers, educators, advocates and visitors. We are responsible to asking questions of ourselves in this moment and know that they will be asked of us.

In times of pain and trauma, we also know that art and creativity are a form of healing and hearing, resilience and resistance, and that creativity and invention help lead us forward.

Together we seek equity, solidarity and the breaking down of systemic racism and injustice. Send us your hopes and dreams for your community, for the kind of place in which you want to live and thrive. Share your visions related to a future place, a place for climate, justice, wellness and prosperity. Send artwork, music, performances, creative writing, images of handmade signs, photographs, quotes or comments to museum@anchoragemuseum.org and we will compile what we can into an online exhibition/place of sharing.