Art as a Mirror: Sarah Ayaqi Whalen-Lunn on reflecting strength and celebrating imperfection

By Francesca Du Brock, Chief Curator

Born and in Indiana, far away from her mother’s Iñupiaq side of the family in Unalakleet, Sarah Ayaqi Whalen-Lunn’s process of homecoming has been both practical and emotional, unfolding over decades, and since her family moved back to Alaska when she was eight years old. The slow re-discovery of personal and cultural stories and histories has fueled Whalen-Lunn’s curiosity and growth as an artist and ignited her interest in revitalizing Inuit tattoo traditions.

Whalen-Lunn’s mother, Irene Hayes, was born in the tuberculosis home in Juneau. Her siblings grew up in the Jessie Lee Home for Children, and she had only sporadic contact with her mother or her family in Unalakleet. She met Whalen-Lunn’s father, William Hayes, a renowned banjo maker and musician from Maine while he was in the Air Force. Whalen-Lunn’s creative and musical family nurtured her artistic inclinations from a young age. She’s never been much of a “rule person,” largely forgoing formal training and instead choosing to follow her curiosity and learning through a combination of research and trial-and-error. Over the years, she has worked across a spectrum of scales and mediums, from monumental public art installations, to the intimate practice of traditional hand-poke tattoo. She also paints, draws, prints, and makes jewelry.

Left: the artist modeling one of her necklaces. Right: Me and My Dog, 2019

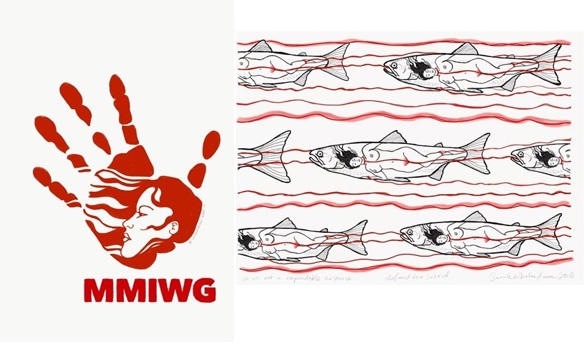

The graphic style she’s honed means she is often commissioned to create stickers, logos, and clothing designs for environmental and social justice causes around Alaska. One of her designs became so popular she recently had to apply to copyright it to discourage its unauthorized appropriation and reuse. The image, showing a red handprint inscribed with the silhouette of an Indigenous woman, was created to honor and bring awareness to the epidemic of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Alaska and across North America.

Left: image of Whalen-Lunn’s design honoring Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women. Right: We Are Not an Expendable Resource. Defend the Sacred, 2018

Often reflecting values of women’s rights, Indigeneity, and asserting the sovereignty of both land and Indigenous peoples, Whalen-Lunn isn’t interested in hiding or dissembling—as the survivor of an abusive marriage and someone who deals with depression, she wants her work to be direct, accessible and honest. She says, “Art is my filter for the world, and the way I can communicate how I’m feeling… I’m not strong verbally but if I can put it out there in a painting or a drawing or a marking or a print…to get people to connect with that emotion, that is important to me.”

Left: Untitled, 2020 Right: Shine How You Want To, 2020

Although Whalen-Lunn has found a commercial market for her prints and jewelry, she is perhaps most well-known for her work in traditional Inuit tattoo. She was first inspired to learn about Inuit tattooing traditions from her close friend and fellow artist, Holly Mititquq Nordlum. At the time, Whalen-Lunn had lots of Western tattoos, but had “no idea that we had tattoos as Alaska Native people, as Inuit people.” The sense of disconnection she felt from her mother’s side of the family fueled her desire to learn more, both for herself and for her three young daughters.

Examples of sassuma arnaa tattoos by Whalen-Lunn

Inuit tattoos throughout the Circumpolar North region historically were made by women, for women. Receiving tattoos was a ceremonial rite of passage that marked important events in a woman’s life, such as the transition from girlhood to womanhood, or the birth of child. Today, the tattoos continue to mark moments of personal importance or transition, while also conveying resiliency survival in the face of generations of colonial oppression.

Whalen Lunn learned the basics of hand-poke and skin stitching techniques from Greenlandic Inuit tattooist Maya Sialuk Jacobsen through Nordlum’s Tupik Mi apprenticeship program. For Whalen-Lunn, tattoo was “a complete game-changer…everything in my life has been touched and transformed by traditional tattooing.” Learning tattoo alongside other women artists forced Whalen-Lunn to confront and dismantle some of the cynicism and standoffishness she’d cultivated through years spent working as a bartender in downtown Anchorage, and through the traumatizing experiences of her first marriage. It taught her to be more open and comfortable sharing her emotions.

One of Whalen-Lunn’s clients showing off her fresh markings, a traditional wedding pattern from Kodiak Island.

This openness is crucial to the practicing of her craft: “you have these young girls coming to you with these hurts and these pains and they’re trusting you with their stories. There are lots of people who have never told their story before, and I’m in a room marking their skin and bearing witness to this, whether it’s pain or whether it’s joy.” Whalen-Lunn describes the trust that her customers place in her as a “gift,” and an “honor,” and something that motivates her to always be better – both as an artist, as also as a human. When asked what tattooing means to her, she says, “it’s a gift. It’s a gift our ancestors left for us. They are breathing [their life] back into us. It’s a healing gift.”

This winter, with support from The CIRI Foundation, the Anchorage Museum will be hosting four virtual artists-in-residence. Follow Sarah Whalen Lunn’s artwork and process through December. Check out her work @inkstitcher on Instagram and Facebook, and tune in to her livestream printmaking demo on the Anchorage Museum’s Facebook page on Wednesday, December 16th at 4:00pm.