Emma Hildebrand: Art as a Process of Connection and Care

By Francesca Du Brock, Chief Curator

Emma Hildebrand comes from a long line of Koyukon Athabascan women who “knew how to do pretty much everything that had to do with survival,” including building cabins, fish wheels, and snowshoes, along with skills like tanning hides, skin sewing and beading. Hildebrand started learning from her mother at around age seven, beginning with simple projects like stringing beads and stitching on moosehide. She made gifts for her family, baby moccasins, barrettes, and earrings. In her late teens, she graduated to larger projects, creating a moosehide parka and a moosehide dress to participate in the Miss World Eskimo Indian Olympics pageant.

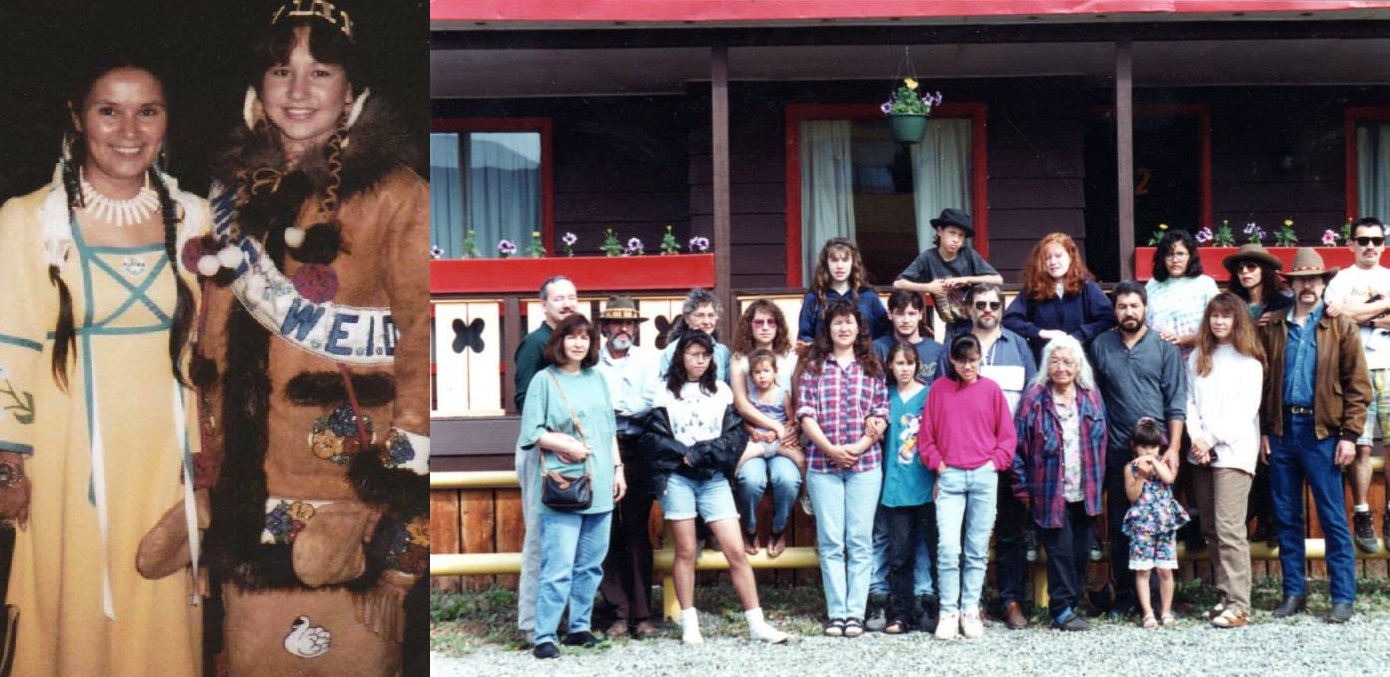

The artist with Audrey Armstrong at the Miss WEIO Pageant in 1981 (left). The artist (seated, with her daughter) and her family, including her mother, in 1994 (right).

Over the years, Hildebrand acquired skills in quillwork and caribou tufting from teachers Dixie Alexander and Nancy Fonicello—techniques she uses today to embellish her distinctive garments and accessories. As a teacher of Alaska Native arts and crafts, she’s travelled the state working with students and passing on valuable traditional knowledge. For her, “being able to continue the knowledge and the crafts through teaching is an honor for me. If someone hadn’t taught me, these skills would not be a part of my life…I teach others so they can enjoy beadwork and crafting and we can continue to preserve our cultures.”

Hildebrand teaching quillwork techniques at the Anchorage Museum.

The materials Hildebrand uses are natural and come from the land. She has a network of friends that help her gather what she needs to make her work. After her mother passed away, she started getting tanned moosehide from her brother-in-law in Northway. She’s also learning to tan her own hides—a project she’s saving for the spring when the weather warms. She prefers not to kill live porcupines herself, so for quills, she keeps her eyes peeled while driving and if she finds a roadkill porcupine that hasn’t been too badly damaged, she stops to harvest the finest, unbroken quills. Friends and family bring her caribou hides, which she carefully scrapes, washes, dies, and prepares for tufting projects. What she doesn’t use herself, she sends out to artists across Alaska and Canada. This extended web of friends, family, and fellow artists involved in making and gathering materials is part of what makes Hildebrand feel connected to her practice and to her community, even during the isolation of the pandemic.

A caribou rendered in porcupine quills on the back of a moosehide vest and a tufted and quilled eyeglasses case.

For Hildebrand, this sense of connection is vital. She says: “It’s not only an artwork, it’s a means of meditating. I sit and I create and I feel good about that, but I also think about family and about life and other things as I’m doing that. It gives me a connection to my ancestors, to people that have passed…” After losing her daughter in 2018, Hildebrand found that her relationship to centuries-old cultural techniques and natural materials had a way of soothing her grief and grounding her: “After my daughter passed, it really helped me get back into life.” Her work is a process of care that stretches both backwards and forwards through time.

Caribou bag with tufted wild rose pattern, 2015, and floral detail on a moosehide dress, created with natural-colored caribou hair, 2017.

Although making art has been an integral part of Hildebrand’s life since she was a youngster, it wasn’t until recently that she began to consider herself an artist. In 2005, after retiring from an 18-year career as the CEO and President of Northway Natives, Hildebrand moved to Anchorage and began pursuing her art more seriously. As teaching jobs expanded along with opportunities to sell her work, she was delighted to find that she could support herself through making artwork. She says that demand for Alaska Native artwork is “exploding” now, but that back in early 80s when she was in school and beginning her practice, it didn’t seem like a viable career. Now, she sees people wearing her work, hanging it on their walls and adding it to their collections. While she admits that she doesn’t often think in terms of labels, the pleasure others take in what she makes has forced her to “acknowledge that what I do is art and that people appreciate it as art. So yeah, I am an artist.”

This winter, with support from The CIRI Foundation, the Anchorage Museum will be hosting four virtual artists-in-residence. Follow Emma Hildebrand’s artwork and process through March. Check out her work @ejhildebrand99516 on Instagram and tune in to her livestream studio demo on April 5th at 12pm Alaska time on the Anchorage Museum’s Facebook page.

Header image: Beaded flowers on moosehide.